CommitLog (aka write-ahead log, WAL) is a standard component of many databases. In Apache Cassandra, it is an efficient append-only on-disk data structure that guarantees durability.

Learning more about how CommitLog works will be helpful to database administrators who want to better understand the guarantees and trade-offs Cassandra provides. This post also serves as an introduction for any users who want to dig into this subsystem. Finally, database enthusiasts and developers might find it interesting to read how Cassandra’s write-ahead log is implemented in practice.

As part of our overview of the CommitLog features, we will go through the following:

-

A Recap of the Write Path

-

An overview of the CommitLog Lifecycle

-

How to Append to the CommitLog

-

CommitLog Segment Types

-

Segment Recycling

-

CommitLog and Change-Data-Capture(CDC)

Write Path Recap

This section briefly summarizes the Cassandra write path to establish the role CommitLog plays in the database system.

When Cassandra accepts new write requests, it saves new mutations to an in-memory write-back cache called a memtable and appends them to the CommitLog. The former allows serving reads without accessing the disk, while the latter guarantees durability. If Cassandra crashes before flushing the memtable, it will restore acknowledged writes by replaying the CommitLog.

Once the database flushes a memtable to disk as an SSTable, which is an immutable file for persisting data, it can eliminate the corresponding log entries. We are going to learn how this happens in the next section.

CommitLog Lifecycle Explained

This section describes the CommitLog structure and how it knows what data to keep or remove.

The CommitLog is an append-only data structure comprising a series of segments - files stored on disk. Segments persist mutations - internal objects containing information about new writes. Besides the changed rows, mutations contain relevant metadata - keyspace and table names, creation timestamp, GC grace seconds, etc. Mutations are idempotent, i.e. Mutations can be applied multiple times while changing the state only once.

CommitLog segments are shared between tables so that all incoming writes land in the same segment. At any point in time, there is:

-

an

allocatingsegment that accepts new mutations -

an

availablesegment to be used next -

0 or more

activesegments to be deleted once the corresponding memtables are flushed.

As soon as the allocating segment exceeds commitlog_segment_size (32MiB by default), the database syncs it to disk and switches to the next available segment. Figure 1 below illustrates different segment types and their function.

Cassandra can only delete a segment after all its mutations are persisted in SSTables. Knowing if a file does not hold any mutations that haven’t been flushed yet requires a bit of bookkeeping.

Each segment maintains a hash table with dirty intervals. Dirty intervals contain mutation positions that haven’t yet been flushed as SSTables. Figure 2 illustrates how the CommitLog maintains dirty positions for each segment.

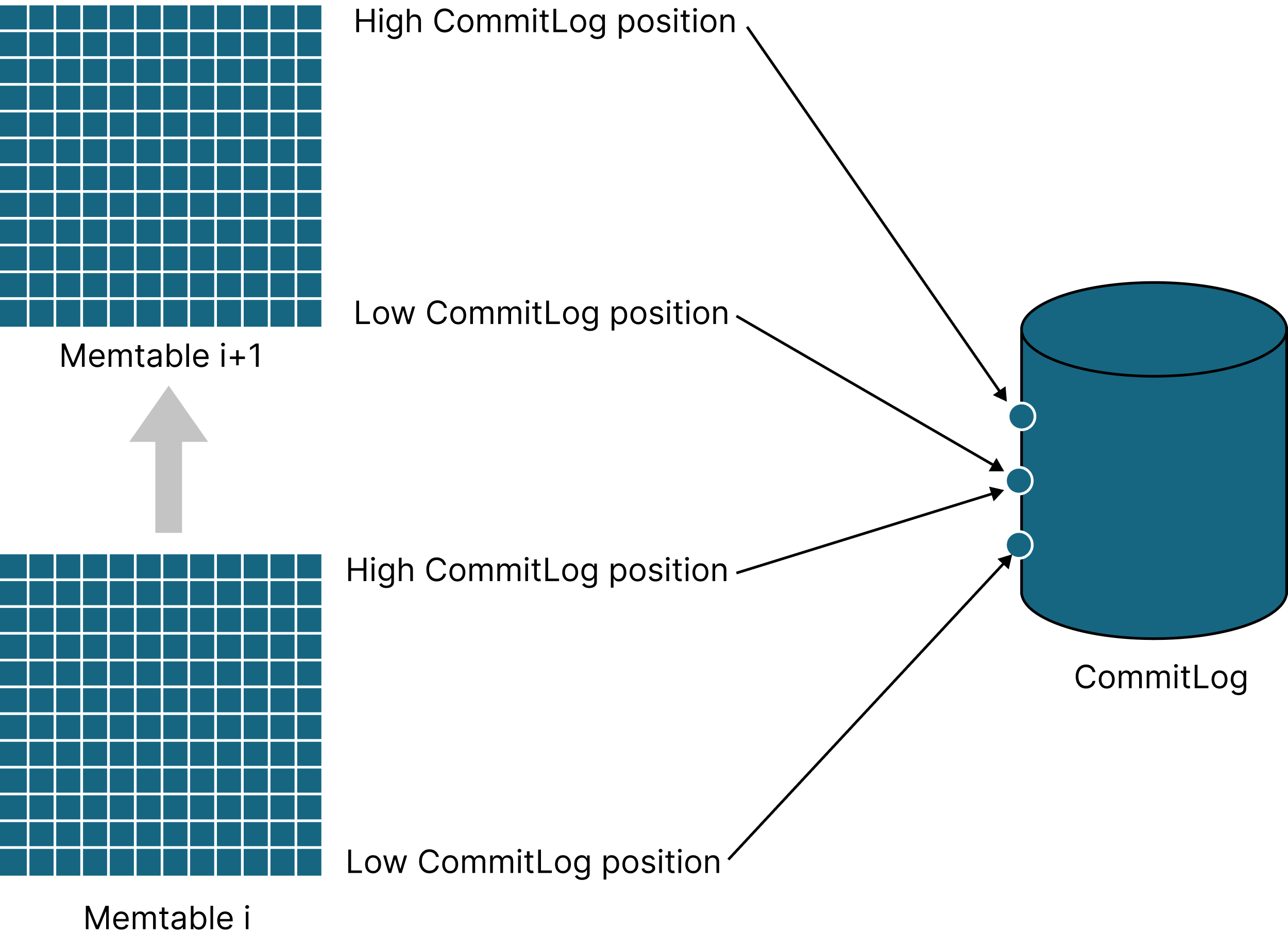

[table id → intervals]. This figure demonstrates a segment with the dirty map equal to { Table 1: [[9, 11)], Table 2: [[7, 9), [13, 15)] }.Each memtable maintains high and low CommitLog positions to mark the corresponding mutations as clean on flush (see Figure 3). The high position is the position of the latest mutation written to CommitLog; memtables update it on each new write. The low position is a high position of a previously flushed memtable. The low position cannot change anymore as that memtable no longer accepts writes.

On memtable flush, Cassandra marks the corresponding CommitLog positions as clean. As soon as the entire segment is clean, the CommitLog deletes it.

Appending to the CommitLog

In the previous section, we learned that the CommitLog appends mutations from different tables to the same segment. The benefit of this approach is faster flush due to sequential write I/O. But doesn’t it create contention when concurrent requests write to the same segment? Let’s see now how Cassandra addresses this issue.

Appending to the CommitLog takes several steps. First, the CommitLog reserves an in-memory buffer in the allocating segment and writes the serialized mutation to the allocated space. Then the CommitLog flushes the entire segment block to disk by calling FileChannel.force().

The only contention point for concurrent writes is allocating space in the in-memory buffer, a relatively fast operation.

Flushing to disk happens according to the commitlog_sync configuration property. It supports the following options:

-

periodic(default) - a write is successful after writing to a buffer in memory. Sync to disk happens everycommitlog_sync_period_in_ms(10,000ms by default) or after reaching the segment size limit. -

batch- a write is successful only after flushing to disk. Every mutation invokes sync (note:commitlog_sync_batch_window_in_msis ignored by Apache Cassandra 4.0). -

group- a write is successful only after flushing to disk. Mutations form a group (hence the name) that waits for the same sync that happens everycommitlog_sync_group_window_in_ms(1,000ms by default).

With periodic mode, the server does not wait for the sync to disk and responds to the client after writing Mutation(s) to the in-memory buffer. While commitlog_sync_period_in_ms acts as an upper bound for the sync frequency, usually, the main sync trigger in workloads for Cassandra is the allocating segment reaching its maximum size. Accordingly, one can decrease the expected time to sync by reducing the segment size controlled by the commitlog_segment_size option. As a side effect, this will reduce max mutation size.

Decoupling of syncing to disk from acknowledging requests reduces an upper bound on throughput and lower bound on latency and provides a trade-off between sync frequency and durability via commitlog_sync_period_in_ms option. A potential data loss scenario for already acknowledged writes is simultaneous OS/hardware crashes on multiple replicas within the sync period.

Alternative sync strategies are batch and group. The batch strategy is essentially a paranoid option that ensures that every successful write is persisted to disk. Rarely required, thorough evaluation is recommended before using the feature. With the group strategy, write requests will be delayed up to commitlog_sync_group_window_in_ms depending on how long ago the previous sync happened. This option allows balancing throughput and latency by changing the window size. A bigger window improves throughput at higher write concurrency while making latency worse as incoming write requests have to wait longer. See CASSANDRA-13530 for more details.

CommitLog Segment Types

The previous section described how CommitLog appends and flushes data. In this section, we will go through what the CommitLog writes to disk, i.e., the structure of CommitLog segments.

Cassandra supports three segment types: memory-mapped, compressed, and encrypted. The database selects a segment type to use depending on commitlog_compression and transparent_data_encryption_options configuration options in cassandra.yaml. commitlog_compression controls segment compression and supports three compression types: LZ4, Snappy, and Deflate. The latter option controls data encryption on disk, including both CommitLog segments and hints. Cassandra uses encrypted segments that compress data before encryption if both options are set. If only transparent_data_encryption_options is enabled, Cassandra uses encrypted segments. When only commitlog_compression is specified, Cassandra uses compressed segments. If neither option is set, the database uses a memory-mapped segment.

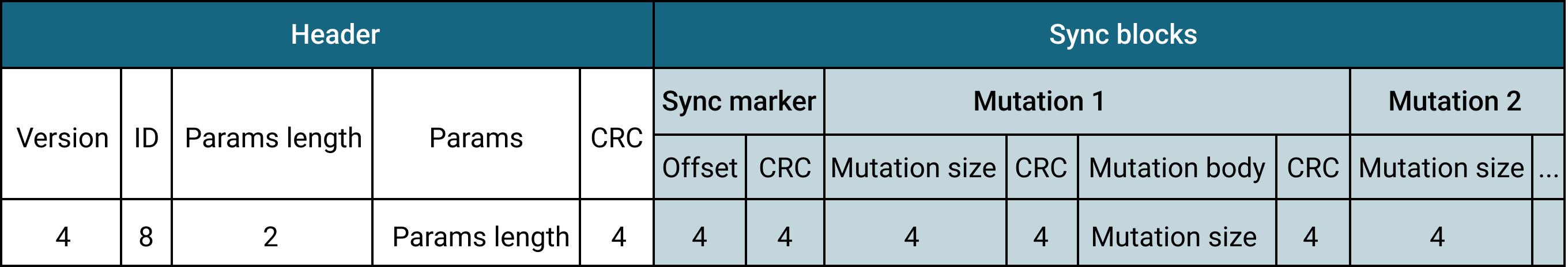

Let’s describe a layout of a memory-mapped segment and build on top of it to show how compressed and encrypted segments work. All segment types use the same pattern. Any data in a segment is followed by its checksum so that readers can discard only corrupted data and recover as much information as possible on error. A segment starts with a header that contains information about its version, compression, and encryption. The header format is the same for all segment types. Sync blocks that follow the header are the CommitLog’s units of write to disk. In other words, every flush to disk creates exactly one sync block. A sync block starts with a marker followed by the mutations. Figure 4 illustrates the segment structure of a memory-mapped segment and describes the purpose of specific fields.

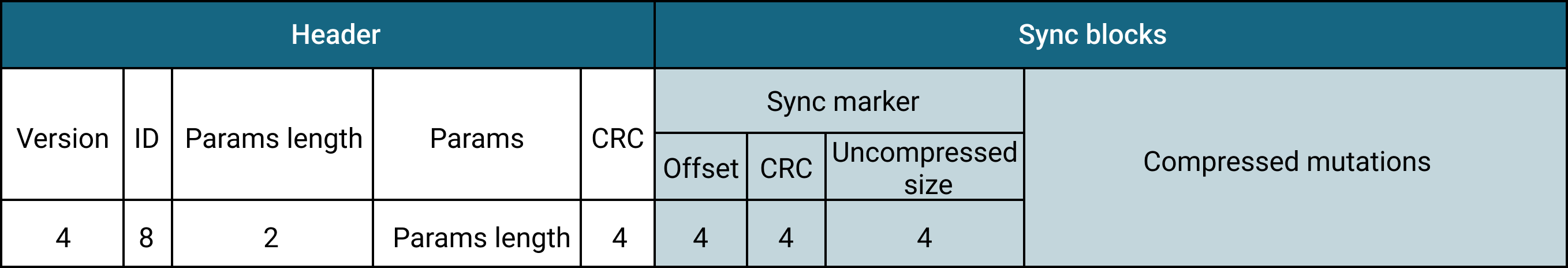

While memory-mapped segments maintain a single memory-mapped file that is periodically flushed to disk, compressed and encrypted segments use in-memory fixed-size buffers to serialize, compress, and encrypt mutations. Besides that, sync markers of compressed and encrypted segments contain an additional value: the total size of uncompressed data. The compressed segment compresses the entire in-memory buffer with mutations before writing them to the segment file. See Figure 5 for the detailed layout of compressed segments.

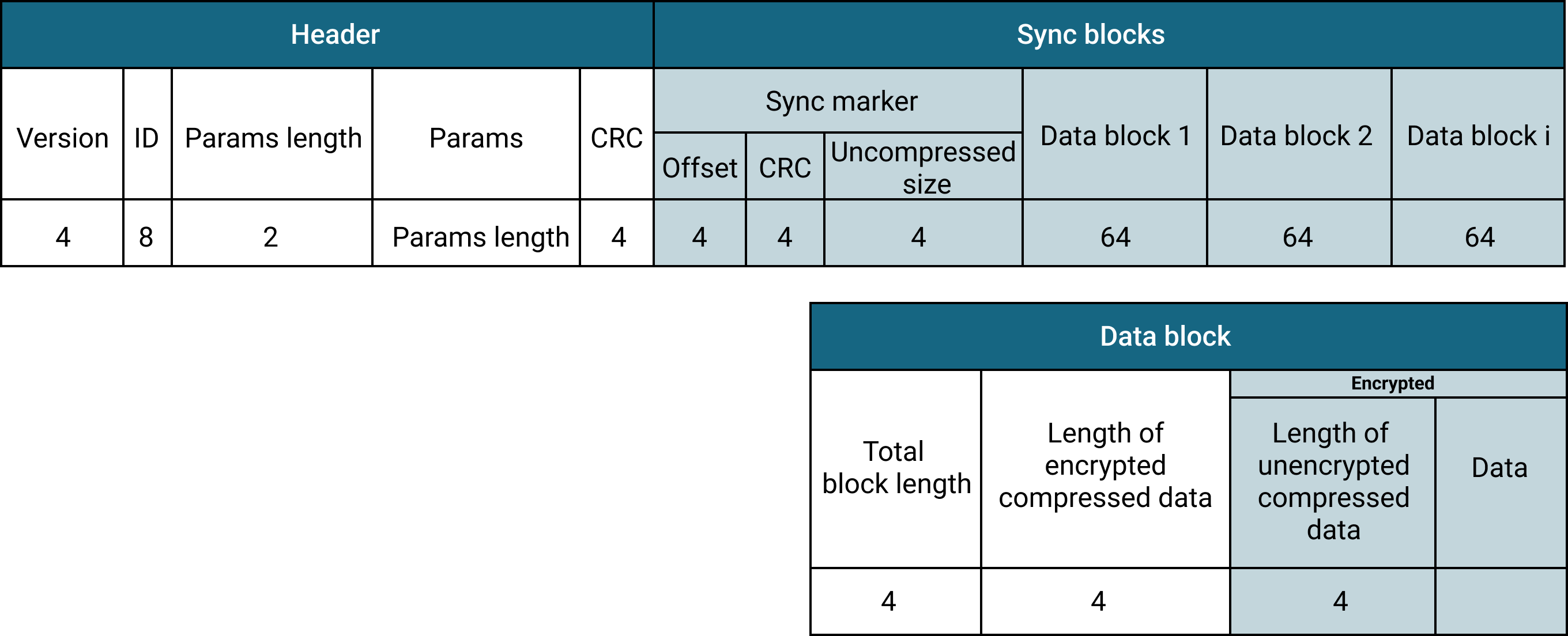

Unlike compressed segments, encrypted segments write mutations in data blocks. These blocks are small chunks whose size is controlled by transparent_data_encryption_options.chunk_length_kb. Each data block is compressed, encrypted, and written to the segment file individually. See Figure 6 for details on the layout of each data block.

Segment Recycling

At this point, we need to clarify the meaning of the term ‘segment recycling,’ which occurs in the Cassandra documentation and the codebase. Segment recycling was introduced in Cassandra 1.1.0 and removed in 2.2.0.

Back in version 1.1.0 (CASSANDRA-3411), Cassandra pre-allocated empty 128MiB files as Commit Log segments. The idea behind pre-allocation was to avoid changing the metadata on append. Accordingly, recycling old segments amortized pre-allocation overhead for subsequent segments. Instead of deleting clean segments, Cassandra wrote an end-of-segment marker at the file’s beginning. New writes overwrote the marker. Restoring from an empty recycled segment was a no-op because a segment reader ignored any content that followed the marker.

Segment recycling was removed in Cassandra 2.2.0 (CASSANDRA-6809). In practice, recycling didn’t demonstrate significant performance improvements (CASSANDRA-8771) while complicating segment lifecycle and introducing non-trivial bugs (for example, CASSANDRA-8729). Starting from 2.2.0, recycling a segment means closing the file and deleting it.

Change-Data-Capture (CDC)

This section describes Change-Data-Capture in the context of the CommitLog and refers to the state of CDC as of C* 4.0 (CASSANDRA-12148). For a complete CDC guide, please refer to the documentation. Change-Data-Capture allows external consumers to consume new writes that happen on the cluster. CDC is configured per-table by setting WITH cdc=true in the CREATE TABLE or ALTER TABLE statements.

CDC in Cassandra exposes synced parts of CommitLog segments to external consumers. On sync, CDC creates a hard link in cdc_raw_directory and a <segment_file>_cdc.idx file. This index file holds the offset for the final byte of the last sync block in the corresponding segment. Consumers should read the segment only until the specified offset as it indicates the point where the segment was safely persisted on disk.

Once the segment is discarded, the index file contains the word COMPLETED. It is the responsibility of the consumer to delete hard links to read segments. If the folder fills up to its max allowed space, cdc_free_space_in_mb, new writes on this table are rejected.

The CommitLog is one of the key components of Apache Cassandra as it offers one of the most important database guarantees: durability. In this article, we covered the CommitLog from multiple perspectives. First, we presented its role in the write path and its interactions with other database components. Then, we discussed the specifics of the sync mechanism as well as relevant configuration. After that, we looked into different segment types and their on-disk representation, as well as the idea of segment recycling. Finally, we briefly covered CDC as a feature enabled by CommitLog.

If you would like to learn more about the CommitLog, you can follow the JIRA issues linked in this article and ask questions on the Mailing List^ and ASF Slack in the #cassandra Slack channel.

Thanks to Frank Rosner, Branimir Lambov, and Chris Thornett for their discussions and corrections.